Making of a Puran Poli Identity

Rakshita

Deshmukh

SYBA

2019

|

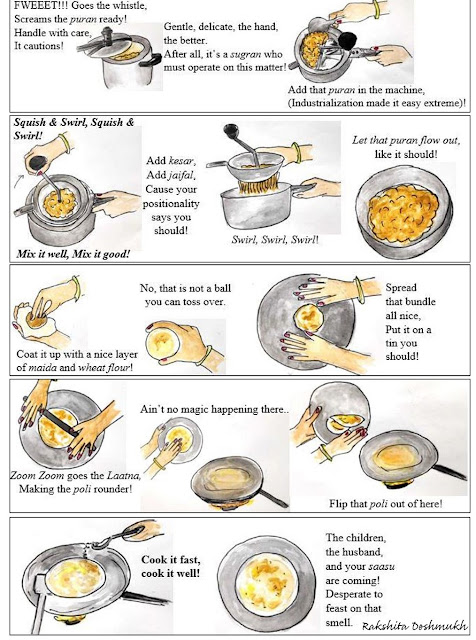

| Making of puran poli. |

Now that the puran poli is made, let’s explore the aspects that blend in with the consumption of this celebrated dish. Puran, in its literal terms, means stuffing. Made with a mixture of chana dal and jaggery, puran and its consequent puran poli is a traditional Maharashtrian dish (Kadbhane & Giram, 2019). The essentialism of this dish is enumerated by symbolising it to constitute prestige and to bring in prosperity on days of festivals such as Holi, Gudi Padwa, Ganesh Chaturthi, and weddings.

Puran poli with cold milk reminds me of comfort and of home. It makes me nostalgic, taking me back to the memory of being thrilled at the swirling process of the puran poli machine. It reminds me that though my hold on the Marathi language is not strong, I can still defend my cultural identity through my love for puran poli.

My maternal grandmother told me that not every caste makes the poli with tin plate and oil. It is only distinctive of a CKP (Chandrasenya Kayastha Prabhu) member. The access to machines is guarded by status and possession of capital. The ingredients are distinct, wherein the upper class adds kesar and jaifal to the puran resembling their superior privileged access to the two commodities. Brahmins make polis out of rice, while other castes make it out of wheat.

Puran poli is highly home based, it has not been capitalised yet. The exclusivity of this resource despite being within the context of popularity is essential in creating continued demand. This dish cannot be readily accessed in the way one can get a Dosa even at a specialised North Indian restaurant. The aspect of access comes with the notion of authenticity. There are few local shops who keep this dish for sale. Yet the quality, as my grandmother describes, is not “Marathi enough” for the dish to sell. The authenticity could be subject to constraints such as resource availability and cost of production, however, the need for being ‘homely’ is perceived to be more important. Making of this dish observes rituality in the sense that prior to a big festival, my mother who always sleeps at 10 p.m, spends the entire night cooking and making the polis.

Food as a commodity is perceived to be economised even within the realm of home space wherein the food is prepared specifically to satisfy a particular individual in expectation of an exchange. My mother cooks puran polis for her extended family in hopes of attaining ‘punya’ and blessing from God. This selfless act of hers can be seen as a transaction wherein her preparation of the food item is in exchange of the invisible ‘punya’ she seems she will gain.

One’s cultural identity is embodied and defended through food since food is a visible physical manifestation of cultural being. We encode information around us through segmenting into events (Kurby & Zacks, 2008), to an extent that information regarding our day will be stored in terms of specific categories/folders. We tend to find cues to represent this information for long-term memory to encode it efficiently. I see food as a cue to assist in encoding, retrieving and remembering one’s identity.

There have been studies attempting to develop instant mixes for puran. The premix has been established in such a way that the dry powder requires only water to be made (Kadbhane & Giram, 2019). Similar to MTR’S ready-to-eat mixes which are loved by those away from their physical spaces of identities. The usage of banana leaf instead of tin was more prominent earlier. Industrialisation and globalisation has made the tasks of making this dish convenient.

However, the aspect of ease is guarded only to those who have the access of being touched by the processes of modernity. The ‘creolization of Indian cuisines’ (Mish, 2007) has brought up western-ity within Indian foods. The machinery used to make puran are made of steel, which wouldn’t have been possible without the 200 years of colonial subjugation. The western thought of following a diet, increased awareness of gluten and taking protocols towards a healthy lifestyle has also created creolized Indian foods. My mother often tries to make authentic Maharashtrian food Keto-friendly. Cooking the poli on ghee instead of oil, using almond flour instead of wheat is the classic solution of substituting healthier food choices within traditional context. It creates the illusion of having something close to your identity.

|

| Hot puran poli on the tawa. |

Puran poli is only prepared by the women of the house. Since women are perceived as a commodity using their labour to produce output, there is an alienation of women from family ties with their movement restricted to the kitchen. Having a working mother and the access to a house help, the alienation and the supposed woman’s duties do not seem to diminish. My mother continues to be in the kitchen. She is praised for her cooking and called a “sugran” by my grandmother who praises her kitchen work more than her career achievements.

The monopoly of producing puran polis lies in the hand of my mother, whom I feel is a “responsible gatekeeper” (Mish, 2007). Though the production and choice of food is often ordered by my father and her children, the control and execution lies with my mother. I think that despite being perceived as powerless in a patriarchal context, women of traditional conformity embody power in terms of controlling the consumption of the family. Dietary controls of the husbands might be perceived as care but there is a sense of authority in making decisions for them.

The aspect of purity dwells in the production of puran poli. They are only made by one women of the house. The dynamic between my mother and grandmother is such that the both of them never cook together. They may cook in the same kitchen but always prepare separate dishes. There is often a sense of competition among them, despite both of them being victims to patriarchy.

Cross-cultural references to this dish has been instilled in description of the food. With urbanisation, the different cultural spaces have been required to blend in and share knowledge with each other. The ‘food boundaries are dissolving’ (Appadurai, 1988) with dissolution of concrete spaces of residency. The originally perceived “Other” and its “Otherness” through its value systems and reproduction of food commodities continues to be seen as a repertoire of a particular distinct identity, however, this creation of distinctiveness does not limit access to its gems such as the puran poli.

A shared space of education, workspace, and demanded team-works brings in the habit of sharing values and food. In several search engines, the understanding of puran poli has been accommodated through the preferences of the English language, wherein it is often described as a sweet flatbread with lentil filling, or a sweet pan baked paratha (Kadbhane & Giram, 2019; Kardile et al, 2018). The dish is nowhere close to being called a bread or a paratha, the latter being usually more savoury. This “cross-ethnic urban interaction” (Appadurai, 1988) to explain a regional dish showcases the thought to invite inclusion.

To understand the relationship this food item has with others, I interviewed a few of my friends and relatives, primarily asking them two questions; a) Apart from consumption, what is the significance of Puran Poli to you? And b) how do you view your cultural/communal association in relation to this item?

For those who explicitly declared their association to being a Hindu Maharashtrian, stated awareness of their position in terms of the class-caste structure to be higher in the hierarchy. They reminisced how puran poli is a signifier of festivals, of a “warm fuzzy feeling of comfort”, and a sense of prosperity. One of them also commented on the use of excessive ghee in her family, which for her symbolised a sense of privilege. The process of making it from scratch portrayed the notion of purity since she made all the ingredients at home. Further, the puran poli is paired with the bi-product of the puran used to make a spicy, thin curry (kata chi amti) which for her makes the meal complete. Though I have been consuming the dish with cold milk, the thin curry that my friend is accustomed to symbolize the variation in the dish and identity.

Those who did not identify as Maharashtrians, said that having grown up in a State as well as belonging to it, has embedded in them an appreciation of the dish. They associate the dish to their upbringing in Maharashtra than their cultural identity. One of them even termed the dish to be on the same level as their comfort food. The role of dominant state culture has an impact on the perception of its products wherein non-conforming people seem to accommodate them while being a part of their own cultural space. An intersectionality lies within the physical space of belonging and food.

The processes of modernity and access to variety has made consumption devoid of attuning to a communal identity and to a rigid structure. The cycle of inherited and observed consumption- ritualism has been embedded in making a food item prestigious to conformers as well as non- conformers of a specific identity.

References

Appadurai, A.

(1988). How to Make a National Cuisine: Cookbooks in Contemporary India. Comparative Studies in Society and History,

30(1), 3-24. Retrieved January 26, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/179020

Kadbhane, V.N., & Giram, K.K. (2019).

Preparation of instant puran poli premix powder.

Journal of

Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 8(1),

1125-1128.

Kardile, N.B., Nema,

P.K., Kaur, B.P., & Thaker, S.M. (2018). Fuzzy logic augmentation to

sensory evaluation of Puran: An Indian traditional foodstuff. The Pharma Innovation Journal, 7(12),

69-74.

Kurby, C. A., & Zacks, J. M. (2008).

Segmentation in the perception and memory of events.

Trends in

Cognitive Sciences, 12(2), 72–79. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.11.004

Mish, J. (2007). A Heavy Burden of Identity:

India, Food, Globalization, and Women. In Belk,

R. and Sherry, J. (Ed.), Consumer Culture Theory (Research in Consumer Behavior, Vol. 11),

Emerald Group Publishing Limited,

Bingley, pp. 165- 186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-

Amaze! So very well put! Puran Poli indeed gives the feeling of home. ❤️

ReplyDeleteThis is an awesome post Rakshita 😍 I'm craving for puran poli now 😝🙈

ReplyDeleteGreat post Rakshita!

ReplyDeleteWOAHHHHH!!! Such great insights! Love it considering the fact that I just ate a puran poli🙌

ReplyDelete