Mickey Mouse and the Shadow of his Legacy

TYBA, 2020-2021

Mickey Mouse- a drawing that went on to change how the world would look at cartoons and films. The world adored him so much that he became the first ever animated personality to get a star on the Hollywood walk of fame. A Hero, a Soldier, a Celebrity, a reflection of American values, a Capitalist, and the King of Merchandise. Mickey Mouse became a family name and his iconic Mickey Ears became synonymous to childhood, imagination, and “happily ever after”.

When the world first saw Mickey, he was misbehaved, he did not represent the ideal American values or morals, he caused chaos, so the question is-

(Parody of Alexander Hamilton from the musical ‘Hamilton’)

How does a smoker, shooter, son of a failure

And a rodent, dropped in a middle of a comic strip

Challenged by Charles Mintz

get published and featured, grow up to be a hero and printed on T-shirts?

The billion-dollar, founding father for the company of his father

Got a lot farther, the Brave little tailor

By apprenticing for a sorcerer

By being a self-starter

By 1970s, gets on the hall of fame, the first fictional character

And every day when cartoons were being drawn and animated away

Across the ratings, he smiled and he kept his

charts up

Inside, he was giving the world something to be a part of

Walter wasn’t ready to beg, steal, borrow or barter

Then WWII came, and devastation reigned

Our man saw his future, grip gripping down the memory lane

Walt put a pencil to his temple, connected to his brain

And he sketched Der Fuehrer's Face, a testament to ‘Merica’s glory days

Well, the word got around, they said, this Mouse is insane, man

Took a couple more cartoons and established a Disneyland

Get your monetization, don’t forget the copyright claims

And the world is gonna know your name

What’s your name, man?

Meeska Mooska Mickey Mouse!

If one has to stay true to the spirit of Disney, a song to represent the evolution of a character is a must. The parody above traces how Mickey Mouse went from a petulant, badly behaved, scrappy cartoon to a dramatically different character with childlike innocence and heroic morals. As Mickey started gaining popularity, Walt Disney wanted to get rid of the misbehaving side of Mickey, to tame him and make him more realistic for the audience to accept him. Major changes of adding pupils to his eyes, changes in his size and shape were made, he became more overtly childlike in appearance (Miller, 2009) but what remained were the iconic Mickey ears that retained the essence of the original Mickey Mouse.

From then on, Mickey became not just a fictional cartoon but also a character in a real world with whom America could relate to. A world where horrible things were taking place, but the fearless mouse with a heart of gold walked through those adversities, went on adventures and made it through successfully each time. Mickey became a representation of what the American society dreamt of- happily ever after. Walt’s and Mickey’s story became synonymous with the American Dream and were celebrated and recognized by children and adults alike.

A study conducted on logo recognition showed that by the age of six Mickey Mouse’s Silhouette was recognised by nearly 90% of the children (Houston, Fischer & Richards, 1992). Children showed recognition of the Disney product logos without batting an eyelid, and the iconic Mickey Silhouette became recognised through its presence in the merchandise market.

Watches that Captain America: The First Avenger star Chris Evans was spotted wearing on a red-carpet event, Mickey stuffed toys, bedside lamps, even Mickey telephones made their way into the consumer market. The products branded with the trademark ears became unavoidable, and it is important to mention that this merchandise storm started during The Great Depression. Mickey provided the masses with hope and happiness through his comics, films and shorts, the audiences thus consumed products with his brand even during The Great Depression in hopes of finding their happily ever after*.

Mickey’s popularity spanned across generations, and constant efforts were made to keep it that way. In the 1980s Mickey appeared in video games, presenting himself to the newer generation. The company monetized largely on the Mickey Mousecapade by Nintendo (Miller, 2009). More recently, Mickey made memorable guest appearances in the Kingdom Hearts series and has ensured that his symbolic ears remain in the public eye. Mickey Mouse made sure he connected with his audience even during a global pandemic. Children could call on a certain phone number and either Mickey or one of his friends would tell them a bedtime story.

Moreover, Disney recognised the cry of people stuck indoors, who claimed they missed visiting Disneyland. Disney published recipes of their classic dishes on The Disney Food Blog. Mickey shaped pancakes, waffles and churros then provided people with the same comfort that the magical land provides and gave them a sense of solace during the dreadful pandemic. Even though the dishes may not taste exactly like the ones in Disneyland, they at least looked like it. Just the symbol of Mickey’s shadow was enough for people to connect with “The Happiest Place on Earth” and as Baloo from The Jungle Book expresses, to “forget about the worries and their strife”.

Mickey thus represents the hopes, values and dreams of the people. The use of Mickey during the second world war as a symbol of the US, its values of freedom and independence played an important role in strengthening Mickey’s relation with pop culture. The people made an active choice to bring him into their homes, whether the products met their needs or not did not matter, they resonated with their values and desires and that’s what made America fall in love with Mickey, and the world soon followed. Disney started global marketing. Even Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein once declared that Mickey Mouse was America’s most original contribution to culture (Forbes, 2003).

It is fair to say that popular culture encourages capitalism, it makes profit based on market reactions and profits based on people who fetishize commodities. The community formed in this case are known as the ‘Disnerds’. However, the products that cater to the ‘Disnerds’ are a part of the elite, high culture. Disney’s jewelry line collaboration with Pandora and Disney weddings are an example of how this icon of the masses, serves the elites. The trend of finding the “hidden Mickey”, three circles that form Mickey’s silhouette, in Disney hotels is a leisure activity experienced only by those who can afford that luxury. However, to make sure everyone in the world gets an opportunity to spot the “hidden Mickey” and in order to keep the masses in the chain, Disney makes it a point to sneak a hidden Mickey silhouette in their movies for the audiences to spot and play along.

One question that remains is how Mickey Mouse managed to remain relevant over international boundaries, through nine long decades. The answer is through building Storyworlds (Forbes, 2003).

Media creators learned to conceive fiction not as single products, but as series of larger narratives that thrived on the building of imaginary worlds (Forbes, 2003). Which meant building an intertextual world where characters from one text could support the story of a character from another text and vice versa. Thus, when Mickey appeared in comics other than his own, it established a larger story world, much like the Marvel Cinematic Universe. When Mickey appeared in Goofy’s solo comics or when Donald Duck appeared in Mickey’s, it gave the audience an idea of a larger world where these characters are situated. This intertextual buildup of a story world that the audience consumed, linked them to Mickey Mouse and it ensured the familiarity with the anthropomorphic Mouse and his friends. Wasko (2001) writes that “from its inception, Disney created strong characters that were marketed in various forms (mostly through films and merchandise) throughout the world”.

This also indicates how these characters reflected values that the world could relate to and wanted to see more of, be it on screen or on their keychains.

We can see how this intertextual storyworld with strong, popular characters then shook hands with consumer culture and ensured that Mickey became a brand not just enjoyed but also extensively consumed. Thanks to consumer culture, Disney started mass manufacturing products, with the help of industrialization it started producing more choices which encouraged consumption, which in turn kept demand, supply and production at higher levels.

Mickey Mouse appeared across stories and media. In comics, television and movies. His comics featured caricatures of celebrities from the real world. This boundless amalgamation of the real and the imaginary into a single fictional storyworld which the consumers were allowed to enter even literally through Disneyland made Mickey a global Popular Culture artefact to enjoy, to relate to and to consume. Disneyland became a physical embodiment and a simulacrum of this plausible impossible where lines between fantasy and reality were blurred**.

The idea of The Plausible Impossible comes from Walt Disney’s unfinished book The Art of Animation where he theorised that one can take something that is against the law of nature, something impossible and make it appear rational and acceptable, in short, possible. ("The Plausible Impossible", 1956). Disney used this idea by distorting reality and creating a hyper reality that is real and unreal at the same time. For instance, the celebrities in Mickey’s Gala Premiere were all too real, however Mickey interacting with them is the plausible impossible. Similarly, Disneyland’s Magic Kingdom, Fantasyland, Tomorrowland and Adventureland is a physically real environment but in many ways is unreal. With the waterfalls and wooden bridges in Adventureland, the presence of spaceships and stormtroopers in Tomorrowland, the fairy-gardens in fantasyland and the entire replicated façade of Mainstreet USA in The Magic Kingdom. It is a simulated environment of hyper reality.

The Disney silhouette is itself a simulacrum of everything Mickey Mouse represents. It replaces the reality of a cartoon drawing with a representation of what the drawing has grown to symbolise. A representation of childhood values, of a dream come true, just like Disneyland.

Disneyland popularized the Mickey silhouette further through the famous Mickey shaped balloons, ice creams, hedges and even Mickey printed clothing. Disneyland also provided for a larger market to sell Disney branded merchandise which spanned across price ranges, catering to a range of income brackets. Thereby maintaining its popularity as well as exclusivity.

Economist Thorstein Veblen’s hypothesis of non-satiety suggests that no person can ever be satisfied with all that they consume. Those who have the power to consume, will keep consuming. Those who don’t will continue to attempt to reach that level of consumption by emulating the elites. For example, the YouTubers on the channel The Super Carlin Brothers have an extensive collection of non-sponsored Disney mugs. Their mug collection influences their subscribers to start their own collection to showcase their love for Disney. Their collection may not be as extensive as that of the YouTuber’s but they will still make an effort to buy at least one mug to prove their love for Disney.

The audience is able to take aspects of the storyworld home in the form of merchandise and consume it in their daily lives. Disney thus became an undisputed pioneer in marketing and created an all-encompassing consumer environment that Walt Disney himself described as “total merchandising” (Vaughn, 1995).

This complex process of creating a storyworld with intertextual links that spread across media was quintessential for Disney’s success in the merchandise market. With the establishment of the Disney theme parks and resorts across the globe, Disney became a global icon. The three circles are now recognized across the world and represent a set of values and nostalgia which Disney has been overwhelmingly successful in capitalizing.

Television shows such as Mickey Mouse Club House gained tremendous recognition in India and marketed itself as an entertaining and an educational show. It made a remarkable impression on children, thereby making its way into the memories of the newer generation.

The Mickey Mouse Silhouette no longer only represents the mischievous Mickey. It now is a symbol of everything Disney as a company creates, values and sells. Disney has evolved from a studio creating animated cartoons to that of an influencer in changing values in times as crucial as the world war to creating a leisure market of TV shows, streaming services, tourism and consumer merchandise for audiences across gender, race, age and class.

Though problematic in many ways, Disney has ensured its social presence of innocence and has maintained the idea of ‘The Happiest Place on Earth’ for decades now. One may like it, one may hate it, and as frightening as it may sound, there is no escaping it, at least not for a few more years and certainly not for the next few months with Disney Celebrating Mickey Mouse’s 93rd birthday in November, 2021.

These three circles have come to embody the spirit of creativity, imagination, dreams and aspirations alongside consumerism, monopoly and capitalism. It is a symbol of an entire empire created and marketed under Walt Disney. An enterprise “that it was all started by a mouse” ( Walt Disney, Disneyland; October 27, 1954).

I would like to conclude this essay with yet another parody of a classic Disney song When you wish upon a star-

When you wish upon a simulacra

Makes no difference who you are

Anything your heart desires

Will be sold to you

In your wallet is your green

No request is then extreme

When you wish upon a simulacra

As consumers do

Image courtesy- clipart-library

NOTES

* For more regarding this topic read about the relationship and paradox between Mickey Mouse, Disneyfication, and the Great Depression. https://severnhistoricalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/3-history-thesis-paper.pdf

** The simulacra, according to Jean Baudrillard, are the significations and symbolism of culture and media that construct perceived reality. It contributes to the acquired understanding by which our lives and shared existence are rendered “real” and legible.

REFERENCES

Bemis, B. (2018). Mickey Mouse morale: Disney on the World War II home front. Retrieved 18 September 2020, from https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/ww2-disney#:~:text=Disney%20was%20most%20prolific%20during,in%20the%20U.S.%20armed%20forces

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Disneyland television program. (1956). The Plausible Impossible [TV programme]. ABC. Retrieved 19th September 2020, from https://vimeo.com/233238642

Forbes, B. (2003). Mickey Mouse as Icon: Taking Popular Culture Seriously. Retrieved 18 September 2020, from https://wordandworld.luthersem.edu/content/pdfs/23-3_Icons_of_Culture/23-3_Forbes.pdf

Generations, 1. (2020). Mickey at 90: how one of the world’s biggest pop-icons has stayed relevant for generations — Blanck Digital. Retrieved 19 September 2020, from https://www.blanckdigital.com/mickey-at-90-how-one-of-the-worlds-biggest-pop-icons-has-stayed-relevant-for-generations/

Gillett, B. (1933). Mickey's Gala Premier [Film]. United States: Walt Disney Productions.

Harris, P., Reitherman, B., & Gilkyson, T. (1967). The Bare Necessities. Disneyland.

Houston, T., Fischer, P., & Richards, J. (1992). The public, the press and tobacco research. Tobacco Control, 1(2), 118-122. doi: 10.1136/tc.1.2.118

Christie, J., & Brant, M. (2018). Walt Disney Company’s Effect on American Culture Throughout the Great Depression and World War II.

Miller, M. (2009). Disney Epic Mickey. Retrieved 18 September 2020, from https://www.gameinformer.com/product/disney-epic-mickey

Vaughn, S. (1995). Christopher Anderson, Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the Fifties. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994. 343 pp. American Journalism, 12(3), 404-405. doi: 10.1080/08821127.1995.10731755

Wasko, J. (2001). Understanding Disney. Cambridge: Polity Press.

IMAGE CREDITS

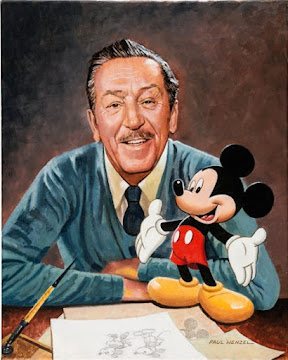

Wenzel, P. (2018). Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse Painting.

Comments

Post a Comment